Ukrainian article of the week published in the 56th edition of the "What about Ukraine" newsletter on November 28th, 2024. The article was written by Anzhela Anisimova for Ukrainer.net and was translated for n-ost by Natalia Volynets. Find the original article in Ukrainian here.

After decades of prohibition and oppression of the Ukrainian identity, reviving national memory is a very challenging task — especially when it comes to the pages of history that the Soviet authorities tried in every way to amend, silence or destroy.

Even as Ukraine gained independence, many communists, their descendants, followers and Soviet Union supporters maintained power in Kyiv, and it was dangerous for Ukrainian patriots to research and reveal the historical events of their native state, which had been subject to distortion, or had been forgotten. Foreigners were also forbidden to research information about the Holodomor. Soviet authorities ensured that no information about their crimes leaked to other countries. However, many people from Ukraine and other countries studied the famine and helped give these crimes global publicity. Here, we tell the story of a few of those historians who did not succumb to authorities’ oppression and continued their mission to reveal the truth, often risking not only their careers but also lives, to counteract communist propaganda about the Holodomor, even after the USSR had broken apart.

In Ukraine, the declassification of the Soviet Secret Service documents started in 2008, during liberal Viktor Yushchenko’s presidency. When the pro-Russian Viktor Yanukovych came to power two years later, the process stopped. Furthermore, the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation negotiated with the Security Service of Ukraine to coordinate on the declassification of KGB documents in the Ukrainian archives.

This did not happen. Partly, this was due to the efforts of Ukraine’s researchers, whose work attracted attention within the country and further afield to the true history. Many of those making efforts to reveal the truth about the genocide of the Ukrainian people organised by the Soviet government were persecuted, intimidated and fired. But this did not stop them. For example, post-Soviet researcher Petro Yashchuk single-handedly recorded the testimonies of more than 350 people who survived the famine. Activist Oleksandr Ushynskyi initiated the installation of the first monument to the Holodomor victims in Ukraine. Archivist Hennadii Ivanushchenko and his colleagues digitised 57,000 official records from 1932–1933 with data about the causes of deaths of residents of the Sumy region.

It has been no less important to draw foreigners’ attention to these crimes of the totalitarian regime. Despite censorship and restrictions on access to information in the USSR, there still were Holodomor eyewitnesses from other countries, who managed to record and describe these terrible events. For instance, in 1932, Canadian journalist Rhea Clyman travelled thousands of kilometres, including through eastern Ukraine, to write reports for the foreign press about the crimes of the Soviet regime. Austrian Alexander Wienerberger made the only photographs of the Holodomor in Kharkiv, while researcher James Mace suggested the idea of lighting a candle in memory of the victims of the Holodomor of 1932-1933. Below, we tell the stories of these people, who significantly contributed to keeping the memory of Ukrainian history undistorted, and honouring those who were killed.

Petro Yashchuk: Collecting 364 Stories by Holodomor witnesses

Petro Yashchuk was one of the first researchers in post-Soviet Ukraine to share the truth about the genocide of the Ukrainian nation committed by the communist regime in 1932-1933.

Yashchuk hails from the village of Liulyntsi, about 50 kilometres from Ternopil. Having graduated from the Chernivtsi Medical Institute, he worked in the village of Poninka (Khmelnytsk region), first as a general practitioner and then as a therapeutic department head. Apart from his medical practice, Yashchuk spent years collecting Ukrainians’ evidence about the Holodomor.

His studies were independent, with no financial support from the state. After a working day at hospital, he would take his dictaphone and notebook and ride his bicycle through the surrounding villages to find survivors of the Holodomor and record their testimonies.

In 1999, Yashchuk’s collection was published as ‘The Portrait of Darkness. Testimonies, Documents, and Materials in Two Books’ based on transcriptions of audio recordings of the 1932–1933 Holodomor witnesses. These volumes contain the memories of over 350 eyewitnesses, as well as their photographs and copies of relevant documents. In the preface, the author wrote about his work: “Let the pain from the lips of our people be the pain standing in the way of human bloodthirstiness in Ukraine and beyond.”

The book appeared under the support of the Ukrainian philanthropist Marian-Pavlo Kots. The title page, which usually includes the publisher, states two cities: Kyiv–New York. The reason is that Yashchuk’s activities were restricted even during independence: the descendants of the named accomplices to crimes were still in power.

After the publication of ‘The Portrait of Darkness’, the researcher received threats. His apartment was burgled and searched by persons unknown, who broke in at night. They did not want money or jewellery, but were looking for priceless testimonies of eyewitnesses to the crimes of genocide.

To prevent the book from reaching its readers, those in power bought out almost every copy from Kyiv and Lviv bookstores.

Public organisations submitted an application to give Yashchuk the All-Ukrainian Ivan Ohienko Prize granted for merits in establishing Ukrainian statehood, and they tried again, again and again. In 2005, the writer and researcher finally won this prize, and was also awarded the second grade Order of Merit.

Oleksandr Ushynskyi. Researching Ukrainian history for over 30 years

Dissident and activist Oleksandr Ushynskyi initiated the construction of the first monument to the victims of the Holodomor in Ukraine. Since 1994, he has been a member of the board of the National Association of Researchers of the Holodomor-Genocide of Ukrainians, and has been researching the history of the Holodomor for over 30 years.

Ushynskyi comes from the village of Nadrosivka (Kyiv region). He studied at the National University of Bioresources and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv. For three years, from 1985 to 1988, without the knowledge of the communist authorities, Oleksandr secretly collected dozens of testimonies of Ukrainians who survived the 1932–1933 famine.

In addition, he initiated the installation of the first monument to the victims of the Holodomor in Ukraine at a cemetery. This happened at night in 1988, in the village of Tarhan in the Kyiv region. A few hours later, this news spread to the international media Voice of America and BBC. At that time, Oleksandr headed the Tarhan village council. After the event, he was expelled from the Communist Party and lost his job. Hence, he became a deputy of the collective farm head Mykola Barylovych, with whom he installed the monument, and joined the work of the human rights organisation ‘Memorial’, which, together with the People’s Movement of Ukraine, was preparing an international symposium on the Holodomor.

After Ukraine’s independence, Ushynskyi was beaten with weapons twice in the centre of Kyiv. The first time was in November 2011: the unknown assailants knocked him down on Khreshchatyk Street and dragged him into a minibus. For half an hour, the attackers abused him, then took him to the Shevchenkivskyi district police station. At the request of a person in civilian clothes, who refused to give their name, the police drew up an administrative report against the activist.

The second attack occurred in February 2012: a jeep drove by the activist, and marksmen shot twice from the car window. Fortunately, Ushynskyi was not injured. The law enforcement officers never found the attackers in either case.

Even after these two incidents, Ushynskyi continued to do everything he could to ensure that as many people as possible in Ukraine and abroad knew the truth about the Holodomor, and that Ukrainians properly honoured those whose lives were lost, damaged or traumatised by this horrible tragedy.

In 2013, he joined the Euromaidan as a member of the National Resistance Headquarters and a fighter of Company No. 40. In February 2014, he received concussion and bodily injuries. In May of the same year, he joined the Right Sector Ukrainian Volunteer Corps and participated in the defence of Donetsk airport. He joined the Armed Forces of Ukraine in 2015, serving there until February 2017.

Having returned from the army, the activist headed the public Association of War Veterans, Participants of the Anti-Terrorist Operation (OTO), Family Members of the Dead (Deceased) and War Disabled. At his own expense, in the village of Gushchyntsi (Vinnytsia region), he erected a monument to the soldiers of the 131st Separate Reconnaissance Battalion, who died in the Russian-Ukrainian War.

At the same time, Ushynskyi took up museum work. In 2018, he opened a museum in Volodarka village (Kyiv region). He first designed a room with exhibits on the Holodomor of 1932–1933, based on materials that he collected and studied. Later, he recreated a Ukrainian house of those times. The museum also has rooms dedicated to the Revolution of Dignity and the Russian-Ukrainian War.

In February 2022, he volunteered for the army again. He participated in the defence of Kyiv and evacuated residents of Irpin and Bucha. Later, he joined the reconnaissance operations in the northeast of Ukraine. As of 2024, Oleksandr, with the rank of captain, is on reserve, due to health reasons, but he continues to go to the frontline as a volunteer.

Hennadii Ivanushchenko: archiving 57,000 acts

Hennadii Ivanushchenko is a historian and archivist, co-founder and member of the academic council of the Centre for Research on the Liberation Movement, and head of the Ukrainian Information Service - London archive. He was born in the village of Ulianivka, 40 kilometres from the city of Sumy. After graduating from school, he devoted nine years to seafaring, working on fishing and merchant vessels and serving in the Black Sea Fleet. Then he studied history and social science at the Sumy State Pedagogical Institute. In 1999–2000, he was a student of the Ukrainian Free University in Munich. For 15 years, he worked as a history and geography teacher, until he headed the state archive in Sumy in 2005.

After two years at the state archive, as the civil registry books for 1932–1933 were transferred there, Ivanushchenko thought of digitising them and creating an electronic database. After several years of archivists’ work, materials on the causes of death of the Sumy region residents during the Holodomor went public on the state archive website.

These books are important for understanding Ukrainian history of that period, clearly showing how historical facts have been distorted. For example, in most of the acts digitised by Ivanushchenko’s team, the cause of death of Ukrainians was indicated as “unknown”, while the place of their death is “at home”. That is, it was not recorded that these people actually died of famine. Some documents stated the cause was due to “being old” or “from old age”. Sometimes, it was also written “from exhaustion” with a note in brackets “according to the applicant”. The book has several entries indicating that people died on roads. In one document, the cause of death is recorded as “general exhaustion and long exposure to the rain”. In an interview with Suspilne, Ivanushchenko said: “There are unique cases when the diagnoses were counted. In the Nedryhailiv settlement, it is clearly written: 33 percent died from hunger, 30 percent from exhaustion, and 1.4 percent from malnutrition.”

Under Ivanushchenko’s leadership, Sumy archivists managed to digitise 57,000 records. The team carried out such crucial work on their own, in cooperation with foreign colleagues. The state did not thank the archivists, though. Moreover, in 2010, Ivanushchenko was summoned to the regional administration and offered to write a resignation statement, supposedly at his own request. When he refused, the authorities reprimanded him, allegedly because archival documents were poorly preserved under his management. For five months, the authorities looked for reasons to dismiss him. They launched an official investigation, in which he was sent reprimands, all of which were false. These reprimands grew to such a high number, his bosses fired him.The public wrote letters in his defence, but this did not affect the decision of the authorities at that time, whose representatives believed that only by putting “their people” in charge of archives could they control history.

However, the revival of national memory cannot be stopped. After his sacking, Ivanushchenko continues his life’s work. Within the Centre for Research on the Liberation Movement project, he studies and organises the archives of the Ukrainian diaspora in the UK, the US and Canada, while also engaging in educational activities and writing and organising books on Ukrainian history.

Rhea Clyman: reporting on the Holodomor for the international press

Rhea Clyman was a Canadian journalist of Jewish origin who witnessed the Holodomor in Ukraine and reported for the Toronto Evening Telegram and London Daily Express. For her unique accounts from the Ukrainian SSR of 1932, which revealed the truth about the Soviet regime’s crimes, she was expelled from the Soviet Union in the same year.

Rhea was born in 1904 in the Polish town of Połaniec. Two years later, she emigrated to Canada with her parents and two older brothers, where they lived in Toronto. At the age of six, she lost the lower part of her left leg in a car accident. Solomon, Rhea’s father, was also deceased and the family of five children and a mother lacked a breadwinner. So Rhea, at the age of eleven, was forced to work in a factory to help support them. Later, she attended evening courses and classes on entrepreneurship and went to lectures at the University of Toronto.

In 1926, Rhea moved to New York to work as a psychoanalyst secretary. A year later, she sailed to London, where she worked for the Agent-general (a kind of consul) of the Province of Alberta. She soon moved to Paris, hoping to become a journalist. There, Rhea studied French at university. In 1928, as her student visa expired, Rhea went to Berlin, where she learned that her visa to enter the USSR, which she had applied for in Great Britain, was approved.

Aspiring to be a foreign correspondent, 24-year-old Rhea travelled to Moscow, by train. Upon arriving in the USSR, she started to learn Russian and wrote articles for English and Canadian publications. At first, Rhea was positive about the communist society that the Bolsheviks promised to create. Over time, she began to realise how the communist dictatorship actually operated, and noted the scale of terror in the Soviet Union.

Until 1932, the journalist did not demonstrate this break from her positive illusion about the USSR in her reporting. If she had been too critical, her articles would not have passed the Soviet press censorship and this would have threatened her stay in the USSR. However, that year, Rhea’s reports contained criticism of the Soviet regime more frequently. The communist authorities in Moscow responsible for upbeat coverage of the Soviet Union abroad noticed this. The journalist was likely to be spied on by the Soviet Secret Service. Hence, Rhea’s disapproving comments about the considerable difference between the Soviet rhetoric and reality reached the government.

The turning point in Rhea’s journalistic career came in 1932. In June, she set off on a four-week journey from Leningrad to cities in the north of the USSR, such as Murmansk and Arkhangelsk. Through her trip, she wanted to see if political prisoners and exiled citizens of the Soviet Union were used as slaves. A series of five articles about her visit to the town of Kem (on the White Sea coast), which was closed to foreigners, angered the Soviet government. The authorities were also discontent with Rhea for giving her reports to foreign publishers without Soviet censors checking the material. Therefore, the world did discover about the terrible conditions of prisoners’ life and work.

On this journey to the north of the USSR, the journalist travelled more than 1,600 km, and returned to Moscow. In a few weeks, she was on her way again: by car and train from the Soviet capital through the east of Ukraine and mountains of the North Caucasus to Tbilisi. Rhea set out as a guide and translator for two women from Atlanta, Alva Christensen and Mary de Give. Via this journey, she wanted to find out what was actually happening in villages and other Soviet republics, as well as how the USSR citizens lived after 15 years of communist rule.

From Moscow, the three women travelled by car south through Tula, Orel, Kursk and Belgorod. Rhea for the first time saw the famine in Ukraine when they reached Kharkiv, and recounted this experience in her article ‘Girl from New Toronto Begs Bread in Russia. Father Lured by ‘Job’, which was published in the Evening Telegram on 15 May 1933:

“We had been two days in Kharkov, but we were all anxious to get away. The great Ukrainian capital was in the grip of hunger. Beggars swarmed round the streets, the stores were empty, the workers’ bread rations had just been cut from two pounds a day per person to one pound and a quarter. A young Ukrainian girl, Alice Mertzka, had come begging to our hotel for food. She had lived in New Toronto for nine years[,] her father worked for the Massey Harris Company. Three years ago, she and her father came back to Russia to get work at the tractor plant in Kharkov. ‘Now we are without bread’, she told me.”

From Kharkiv, the women drove south along the roads leading through deserted Ukrainian villages. Rhea realised that the empty houses used to be the homes of thousands of peasants and so-called ‘kulaks’ she had met as logging workers while visiting the northern regions of the USSR a few weeks earlier.

Through the Donetsk region and Kuban, the women travelled all the way to Tbilisi, where the journalist was suddenly arrested by the Soviet Secret Service. In 24 hours, Rhea was told to leave the country for allegedly spreading false data about the Soviet Union.

After departing from the USSR, she closely described what she saw during her journey. First, the London Daily Express published several reports in November 1932. Later, in 21 articles, the journalist described a detailed trip published in the Toronto Evening Telegram from 8 May to 9 June 1933.

The series began with an open letter reproaching the head of the Union State Political Administration of the USSR, Genrikh Yagoda, one of the organisers of the Holodomor in Ukraine, as well as the one responsible for mass arrests, executions and deportations to the Gulag. Then, Rhea’s stories about the famine in Ukraine were published. To illustrate her journey, the newspaper made a map for the story titled ‘Toronto Girl’s 5,000-Mile Trip Through Famine Lands of Russia’.

The journalist’s materials are an eyewitness’s chronicle of the Holodomor, which was just beginning to leave its mark on the fate of millions of Ukrainians. Her trip only confirmed the unofficial rumours about the famine that had been spreading since the spring of 1932. In her findings, Rhea did not mention drought or adverse weather as the cause of the crop failure, but clearly pointed to the Soviet policy of food collection that devastated Ukraine and the North Caucasus.

Aged 77, she died in New York in 1981. Her death was not mentioned in obituaries or published announcements despite the significance of her journalistic work for the history of not only Ukraine but, primarily, the global community. Her reports about the famine in Ukraine and the North Caucasus in 1932 were forgotten and removed from the field of view of a generation of Sovietologists and experts in Russian history. In the West, her articles lacked the attention they deserved despite the international attention that her arrest and expulsion from the Soviet Union generated. Still, these texts are valuable materials for understanding the dynamics of the early stages of the Holodomor, while the eyewitness chronicle is a powerful indictment of the totalitarian regime, whose followers tried to deny and cover up their crimes.

Alexander Wienerberger: photographing the Holodomor in Kharkiv

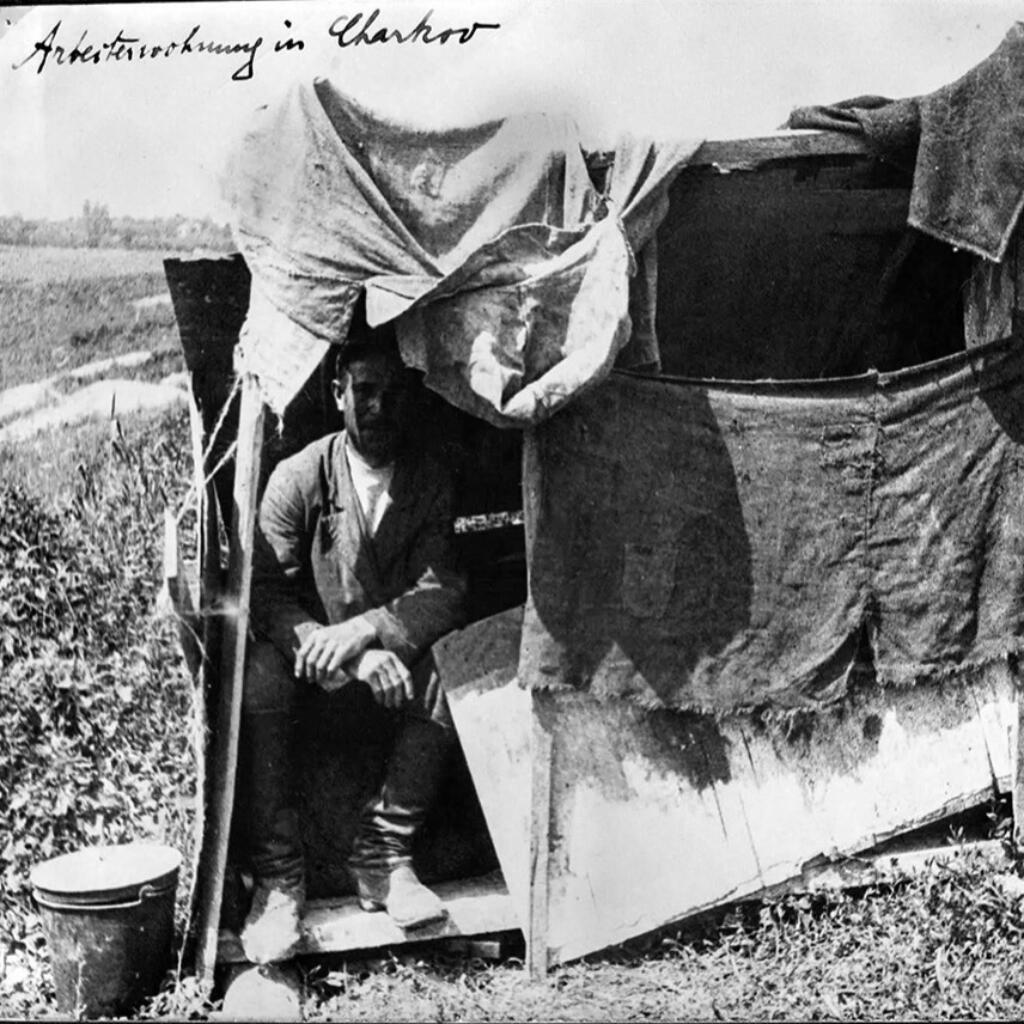

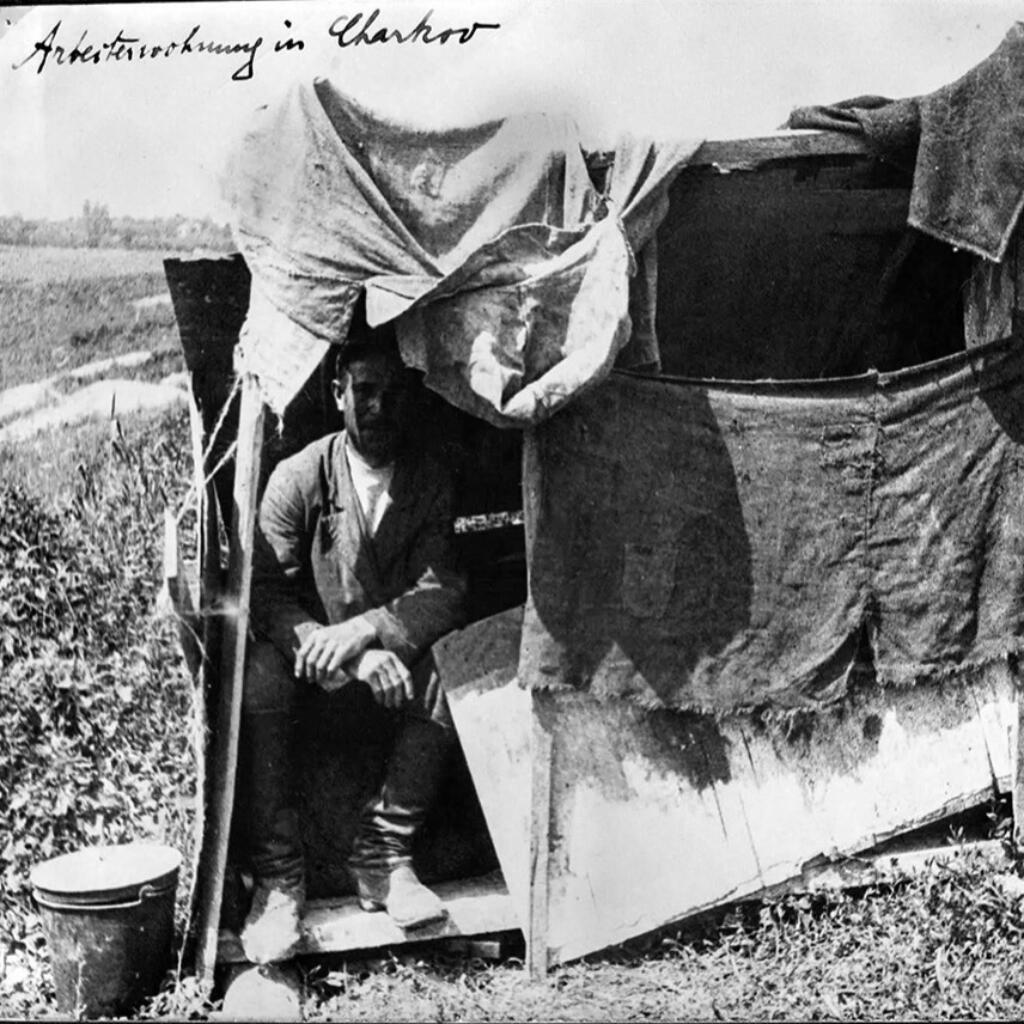

Alexander Wienerberger was an Austrian chemical engineer who lived in the Soviet Union for 19 years. While in Kharkiv, he took pictures of the Holodomor of 1932–1933, which have become the only photographic evidence of the genocide of Ukrainians in this city.

Wienerberger was born in 1891 in Vienna to a Czech-Jewish family. During World War I, he was mobilised to the Austro-Hungarian army. He took part in battles against the Russian army until he was captured in 1915.

In 1919, Wienerberger tried to escape from the USSR with forged documents, but was arrested as a spy. After his release, he stayed in Moscow to develop the production of varnishes and paints. Working in the Soviet Union, he had to travel to various cities of its republics, such as Arkhangelsk, Kursk, Kharkiv, Kyiv, Rostov-on-Don, Astrakhan and Tashkent. The knowledge of the Austrian engineer was so much appreciated that he was assigned to manage the construction of chemical industry plants, searching for raw materials and equipment for them. Thus, Wienerberger could reach locations in the USSR which were generally closed to foreigners.

From Moscow, he was transferred to Kharkiv in 1932: he was appointed technical director of the local ‘Plastmas’ plant, where he worked until 1933. Living in Kharkiv, the engineer witnessed the Holodomor organised by Stalin’s regime. Wienerberger took about 100 photos with a Leica camera of these events.

It was dangerous to take pictures openly in the USSR, and to do this during the Holodomor, Wienerberger used a special removable viewfinder, thanks to which he only had to tilt his head — rather than put a regular camera viewfinder to his eye — to take a photo. This helped him stay unnoticed.

Wienerberger’s first shot of the Holodomor is dated 1933. It shows a man who died of hunger right on a Kharkiv street, and people around his body looking at him. Soon, deaths by hunger became common on the city’s streets and, as the photographer stated in his notes, passers-by no longer paid attention to the dead and walked on by.

Holodomor victim on a Kharkiv street, by Alexander Wienerberger, 1933. Photo credit: National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide.

When Alexander was about to leave the USSR for Austria in October 1933, he sent the negatives of the photos taken in Kharkiv by diplomatic mail through the Austrian embassy. Catholic Cardinal Theodore Innitzer received and saved them in the Vienna Diocese archives. The pictures were first published in 1935 in the book ‘Must Russia Starve?’ by the public figure and journalist of German origin Ewald Ammende.

Four years later, in 1939, the shots appeared in Wienerberger’s book, ‘Hard Times. 15 Years of an Engineer in Soviet Russia. A True Story’ (Ger. ‘Hart auf hart. 15 Jahre Ingenieur in Sowjetrußland. Ein Tatsachenbericht’). Several chapters detailed the Holodomor in Ukraine. Excerpts of these memoirs in Ukrainian were first published by Radio Liberty:

“Before my eyes, again, there is a Ukrainian village where I went in the spring of 1933 in search of casein. Half of the houses were empty, lonesome horses plucked straw from the roofs. But the horses soon died too. There were no dogs or cats, just a bunch of rats gnawing at the exhausted corpses lying around in broad daylight. The survivors no longer had the energy to bury their dead. Cannibalism was commonplace. The authorities did not react to this in any way.”

‘A mother with her hungry children’ — by Alexander Wienerberger. Kharkiv, 1933. Photo credit: Samara Piers’ private archive, provided by Radio Liberty.

The Austrian engineer recalled Kharkiv of 1933, where he lived and worked at the time, as follows:

“Meanwhile, the tragedy continued. Hundreds and thousands of hungry peasants were coming from afar to the city for help, bread, work and consolation. They gathered in flocks in the streets and squares, in the city gardens and courtyards. No one drove them away, but neither did they help them.”

In his book, Wienerberger also recalled Ukraine of 1932, when he was traveling by train from Moscow to Kharkiv. Already then, he noticed the terrible changes:

“The suffering land looked even scarier during the day than at night. At each station, there were countless carriages packed with peasants and their families. They were guarded by sentries to be carried far northwards to their white death. The fields were uncultivated, the unharvested grain was rotting under the autumn rains. […] I didn’t see any cattle or even geese. Only unkempt chickens huddled together near abandoned huts. Involuntarily, I remembered how I, a prisoner of war 17 years ago, travelled through the same country, passing wheat fields, seeing a lot of cattle and mountains of food offered at each station. Even in 1926, after the world and civil wars, these lands prospered like before. How inhuman such a force should be to turn a prosperous food-rich country into ruin.”

‘Queue for black bread’ — by Alexander Wienerberger. Kharkiv, 1933. Photo credit: Samara Pirs’ private archive, provided by Radio Liberty.

Wienerberger died on 5 January 1955 in the Austrian city of Salzburg. More than half a century later, in 2020, a Plast team in Austria found and restored his grave within the ‘Save a Hero’s Grave’ project.

In 1939, with Europe again being on the brink of war, Wienerberger’s memoirs on the Holodomor attracted no global attention. It was only in the 1980s that Ukrainians started talking about the book. In Vienna, it was found by Olexandr Ostheim-Dzerovych, a priest of the Ukrainian Catholic Church, and later by Marco Carynnyk, an American-Ukrainian writer and researcher of the Holodomor and the Holocaust. In 2003, historian Vasyl Marochko published Alexander’s photographs in his work ‘The Hunger of 1932–1933 in Ukraine: Causes and Consequences’.

In 2022, the team of the online publication Istorychna Pravda (Eng. Historical Truth) translated and published the book ‘Hard Times. 15 Years of an Engineer in Soviet Russia. A True Story’. As the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance could not fund the project, they raised the needed UAH 100,000 (around 2,300 euro) on their own. Historian Oleksandr Zinchenko recalls the first day of the collection opened in November 2022:

“Two hours after we announced the fundraising, half of the necessary funds were collected. Emotions and gratitude for donors almost made me cry. When another two hours later over three-quarters of the required amount was donated, I started to giggle nervously: it seemed totally unreal! Just imagine: the country is plunged into the darkness of a blackout, it is the ninth month after the full-scale Russian invasion, all the prices have almost doubled during this time, electricity and banking services are barely working — and in these, to put it mildly, far from fabulous conditions, Ukrainians raise the entire required amount in one evening!”

A preface, biographical sketch, and commentary are to be added to the book so that Ukrainians can become as fully acquainted as possible with the memories of Wienerberger, the only visual chronicler of the Holodomor in Kharkiv.

James Mace: Lighting a candle to his memory

James Earnest Mace was an American historian, political scientist, writer, and Holodomor researcher who moved to Ukraine in 1993. He first suggested the idea of lighting a candle every year in memory of the victims of the Holodomor of 1932-1933. This tradition remains on the fourth Saturday of every November.

Mace’s father came from the Cherokee tribe of native Americans, which the American government forced to move from their native lands in North Carolina and Georgia to Oklahoma in the 1830s. There, James was born (in 1952), attended school, and graduated from university with a bachelor’s degree in history. At the University of Michigan, he received a master’s degree in Russian studies. Under the influence of his mentor, Professor Roman Szporluk, James began studying the history of Ukraine. His doctoral dissertation ‘National Communism in Soviet Ukraine in 1919–1933’, which he defended in 1981, proved the ideals of national liberation to be incompatible with communist ideology.

Mace assisted in the creation of the book by the British historian Robert Conquest, ‘The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine’, which was published in 1986 and appeared in Ukraine seven years later. He also organised a Harvard research programme on the history of the Holodomor of 1932–1933.

For four years, Mace coordinated the work of the US Commission on the Ukraine Famine of 1932–1933, which was created in 1986 thanks to the Ukrainian diaspora. At that time, he not only studied archival documents, but also collected testimonies of people who at different times left Ukraine for Canada and the United States. As a result of the Commission’s efforts, a three-volume book was published based on almost 200 oral pieces of eyewitnesses to the Holodomor organised by the communist regime. In Ukraine, the publication ‘The Great Famine in Ukraine 1932–1933. Eyewitness Testimonies for the US Congressional Commission’ appeared in four volumes in 2008.

In addition, in 1986–1987, Mace prepared a report for the Commission, which was approved by the US Congress. At that time, the Holodomor was called genocide for the first time.

Mace moved to Ukraine in 1993, where he was a professor of political science at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy and continued to research the Holodomor. He also edited the English version of The Day newspaper, where he wrote:

“[F]ate decreed that the victims chose me. Just as one cannot study the Holocaust without becoming half Jewish in spirit, one cannot study the Famine and not become at least half Ukrainian. I have spent too many years studying it for Ukraine not to have become the greater part of my life.”

Mace died on 3 May 2004 in Kyiv. He was posthumously awarded the Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise, 2nd degree. A year before his death, on 18 February 2003 (his birthday), he published an article in The Day titled ‘A Candle in the Window’, in which he wrote:

“I only want to suggest an act of national remembrance available to everyone: on the National Day of Remembrance of 1933 Victims (the fourth Saturday of November), to identify the time when every member of this nation, where almost every family has lost someone close, will light a candle in their window in memory of the dead.”